Strands of chartreuse, gold and sapphire lights reflect off of the dark, rolling currents of the Mississippi River as Lauryn Hill takes the stage. Trading bar for bar with fellow Fugee Wyclef Jean at the forefront of a 10-piece band, the reunited hip-hop act electrifies a swarm of smartphone lights and the occasional cigarette lighter burning into the swampy, southern air.

Occasionally in perfect weather with a brisk breeze blowing off of the water; but more often in between soggy deluges, an entourage of the world’s great musicians have performed for a city that in one way or another helped to nurture them all.

LIZ HOOPER

“You know I did get to rock it with Mr. B.B. King,” Jean says, before bending strings into his own spin on a blues progression that the Haitian hip-hop megastar could have plucked straight from a Beale Street bar a mile away. Energized by the performance and captivated by the appearance of the almost mythical Hill, the crowd began to pulse into a bobbing, breathing human interpretation of the river’s rolling water, forming a captivating backdrop to one of the band’s rare performances since splitting up in the late 1990s.

But this Fugees performance almost didn’t happen.

In October of 2023, the city’s longstanding festival presenter—Memphis in May International Festival—put its 47-year-old Beale Street Music Festival on hiatus. Citing declining attendance (37,000 in 2023 from a pre-pandemic average of about 100,000), a reduced capacity at its traditional home in Tom Lee Park and a $1.7 million repair bill to refurbish the recently renovated 31-acre riverfront park after its 2023 show, the non-for-profit organization suspended the festival indefinitely.

Six months ago, Memphis—the city that harbored the blues, birthed rock n’ roll and fostered cornerstones of modern hip-hop—was left without a signature summer music festival. Last fall, it seemed that May music in Memphis, of all places, would fall silent.

The news set off a tirade of swirling opinions on Beale Street Music Festival’s decline. Some blamed the pandemic. Others blamed an uptick in violent crime in the city. Some blamed newly relaxed state gun laws for bolstering that crime. Many blamed a $60 million renovation of Tom Lee Park, which saw the festival’s footprint transformed from a massive, open lawn into a more developed urban park with built-in forests, playgrounds and basketball courts.

The truth likely lies somewhere between a blend of the above and a shifting festival economy currently juggling market saturation and production costs.

Beale Street Music Festival is not the only multi-day music festival to hit pause on 2024. On the other side of Tennessee, sibling city Chattanooga canceled its longstanding Riverbend Festival for 2024. Philadelphia-based Made in America Festival was also suspended this year. And Colorado’s signature electronic music festival, Sonic Bloom, has followed suit.

But in Memphis, the beat goes on thanks to Riverbeat Music Festival a new, first-year event that defiantly pieced together a modern, three-day event into the footprint abandoned by its forerunner. Headlined by electronic/dance duo Odesza, rapper-turned-bard Jelly Roll and a reunited Fugees, the event was put together in just six months as a test bed for what organizers say will continue an annual Bluff City tradition.

“We’re going to be here,” says Mempho Presents founder Kevin McEniry. McEniry’s company began producing Mempho Music Festival, a smaller, more rock-focused autumn festival in 2017. “The idea is not to make and earn a lot of money. The idea is to try and build something that is sustainable over time and the city can be proud of.”

LIZ HOOPER

Though McEniry’s festival is occupying the same ground as its predecessor, Riverbeat feels markedly different than Beale Street Music Festival. In nearly five decades of operation, Beale Street Music Festival garnered a reputation for blending resplendent Mississippi River sunsets and memorable performances with an opposing quagmire of muddy fields. Indeed, veteran festival goers at Riverbeat can be easily spotted by mud-caked hiking boots still bearing the scars of past years.

A smaller crowd and redesigned park with more sidewalk space, paired with Riverbeat’s seemingly more thoughtful approach to crowd flow, have helped keep the mud this year at a bay. Portable toilets, for instance, are no longer located on grassy fields prone to becoming pudding pits after the first real downpour.

Gone, too, are Beale Street Music Festival’s trio of hulking main stages that often bled sound atop one another. Riverbeat staggers its schedule between two main stages and two smaller stages that allow for an efficient flow between sets. Commutes are relegated to short treks along a riverwalk that is no longer separated from the public via fencing or new, forested paths of some 1,000 native trees planted during Tom Lee Park’s recent remodel.

Tom Lee Park itself, once a backdrop, is now a co-star of the festival. Ample seating areas along the riverfront encourage visitors to sit and sip local brews or lattes beside the swirling water below. A shaded pavilion harboring basketball courts throughout the year doubles as a stand-in for the old festival’s beloved blues tent.

Those touches, along with premium VIP experiences with plush seating in elevated lounge areas, create a less chaotic atmosphere that feels more akin to hanging out with friends in a park that just happens to have a lineup of performing musicians than a dedicated slog through the muddy Beale Street Music Fest of old.

In its first year, Riverbeat’s first year attendance feels light.

McEniry hopes to ultimately draw 22,000 people per day to the three-day event, but Riverbeat is not there yet. They may only be halfway there. If his company is able to achieve their goal going forward, they will still be drawing about 34,000 fewer people than Beale Street Music Festival reported at its peak. But in a world where even professional sports teams are focusing on luxury experiences instead of raw numbers, perhaps a more boutique festival is a new perfect fit.

In this music city, the tailoring is important.

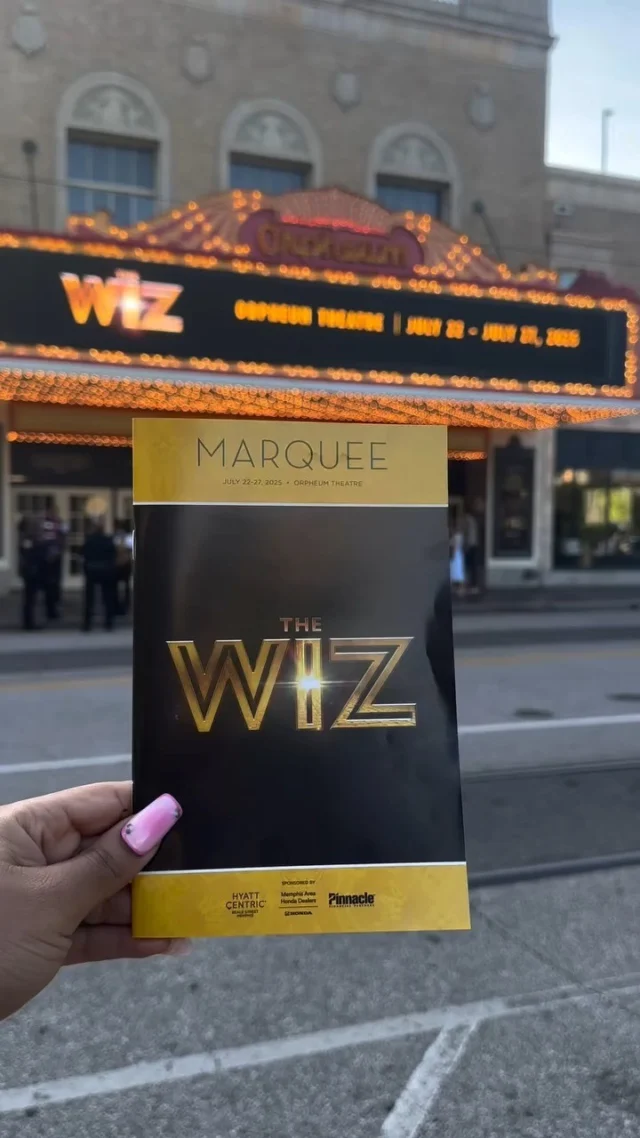

Festivals feel especially significant in Memphis thanks to an unusual civic glitch: Despite occupying the rarest of air among global music cities, Memphis struggles to host the kind of mid-size concerts where many artists thrive. The 18,000-seat FedExForum, home of the Memphis Grizzlies and Tigers basketball teams, is too large for many tours. The 10,000-seat Mid-South Coliseum has been shuttered for decades. 1,700-seat Minglewood Hall, the 2,000-seat Graceland Sound Stage and 2,500 seat Orpheum Theatre— all wonderful homes for more intimate performances—are too small for major tours. A smattering of nearby venues in North Mississippi often host mid-size gigs in the greater Memphis metropolitan area, but outside of its festival scene, the city that birthed much of the world’s favorite sounds currently has few options for many bands that might otherwise perform in the city.

Without regular festivals, Memphis sits at an awkward crossroads for acts drawing more than 2,500 fans but less than 18,000. And that’s a problem.

It’s a problem because people want to hear live music in Memphis. And people will travel to Memphis to listen.

According to Memphis Tourism CEO Kevin Kane, more than half of the city’s 13 million annual tourists are connected directly to its music destinations, primarily Graceland and Beale Street. The former Presley compound at Graceland is still the most visited private home in the United States, luring in more than 500,000 visitors annually. Beale Street draws in an estimated four million visitors per year, regularly ranking as the number one tourist destination in Tennessee despite the marketing buzz of Broadway’s made-for-tv honky tonks in Nashville.

For Memphis Tourism, an annual music festival in May means a jump start on the summer travel season. “We traditionally got a really good jump on the summer travel season because of Memphis in May having their music festival,” says Kane. “The number one reason most people come is in some form or fashion for the music, whether that is for Elvis, Beale Street, Sun Studio, Stax or the International Blues Challenge.

JOE SILLS

“We have to draw in visitors and we need people staying in hotels, buying food and enjoying this event. We want them to build a following so people come back each year.”

On stage, Riverbeat’s coalition of around 50 acts represent a flourishing stroke of the city’s impact on multiple genres. Atlanta hip-hop icons Big Boi and Killer Mike have made the short trip over to answer the call from Memphis. Houston’s Tobe Nwigwe joins the frey alongside honorary local ambassadors to Houston 8Ball & MJG. Nashville-based but Memphis born alt-rock trio The Band CAMINO returns home, recounting tales of May music festivals of old that flew under a different banner. And young blues sensations Southern Avenue share a bill with blues royalty like Robert Randolph, Charlie Musselwhite and Kenny Brown.

“There are a lot of artists here who are internationally known but are from the city of Memphis,” says Southern Avenue vocalist Tierinii Jackson, whose five-piece band spreads a modern blues sound across the globe. “It’s a spiritual experience because of the legacy and the history of the city. The city has thrived because of music culture, and in order for the city to continue to thrive, we need to be pouring into that culture. It’s such a rich history, with so many amazing musicians coming out of Memphis.”

LIZ HOOPER

“You don’t have a lot of cities like Memphis in America,” adds lead guitar Ori Naftaly. “Almost from the moment that microphones became a technology, the most successful music came out of Memphis and this area. Really, from the beginning, There’s something about the energy here, something in the water here where things come together and seem to go out into the world.”

In the crowd, a mingling of curious locals blend with visitors from across the region that have a wider perspective on Memphis. A pair of travelers from St. Louis cite Memphis as a city on the rise while soaking in a parade of paddlewheel steamboats on coursing through a burning, orange sunset. St. Louis has an arch, they say, but fails to utilize its riverfront along the very same river.

“I’m so happy that Memphis has this going on,” says Monica Keshwara, an EDM fan who flew in from Atlanta to experience Riverbeat’s electronic DJ hub, Whateverland. “I moved to Atlanta but I came back just for this event. The river view vibes are the best. I’m going to make out with Odesza tonight!”

“I love the park,” says Memphian Kenn Gibbs, “I’ve been monitoring its progress over the past several years, and it’s amazing now. Walking along the riverwalk while listening to musicians is one of the best experiences in Memphis.”

Jelly Roll fans converge on the festival closer at Riverbeat Music Festival in Memphis, Tenn. on May … [+]

LIZ HOOPER

By day three, the rains have finally caught up to Riverbeat and throngs of weathered, mud-caked boots finally begin to prove their worth.

Facing its first real test against the vengeful precipitation and winds ripping across the river delta, show organizers postpone opening the gates for two hours while storms fizzle out. Newly-elected Memphis Mayor Paul Young joins city folk heroes 8Ball & MJG on stage amidst light sprinkles. But by the time Outkast rapper Big Boi’s Atlanta contingent launches into the title track from 1994’s “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” around nightfall, the deluge returns in earnest.

“It ain’t nothin but a little rain,” belts Big Boi, igniting a Memphis crowd well-versed in the back catalogue of their cultural cousins from Georgia delighting in the throwback tracks from Outkast and a cut of “Kryptonite” from supergroup Purple Ribbon All-Stars.

Big Boi performs “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” in the rain during Riverbeat Music Festival on … [+]

LIZ HOOPER

Big Boi has another surprise for the crowd, too—one that’s become a theme over the weekend—a cameo from a Memphis artist. Grammy award-winning engineer and East High School product Renegade El Rey (fresh off of a Grammy win with Killer Mike’s “Michael” album) launches onto the stage with a spellbinding flow backed by bonafide hip-hop royalty.

Moments later, festival closer and country music megastar Jelly Roll finishes sound check as Big Boi’s crowd migrates stages. Winds continue to percolate over the Mississippi River at stage right as a line of thunderstorms flash over the fields of Arkansas. Stretches of grassy lawn in between newly-minted sidewalks, Pronto Pup stands and beer tents begin to return to their familiar, soggy festival forms of old.

Already amped by an energetic performance from Big Boi, the crowd erupts for the opening chords of the Nashville-based Jelly Roll. Paradoxical in a city that’s about as un-Nashville as they come, Jelly Roll unleashes a torrent of twang over a rock-heavy opening salvo replete with fireballs and smoke machines. A cameo from Jelly Roll’s early career co-star, Memphis rapper Lil Wyte, and an improvised “Mafia!” chant referencing his early fandom to Three 6 Mafia work to win over the few fans unaware of the country star’s background.

“Many moons ago, I used to go to a similar festival right here called Memphis in May,” quips a markedly candid Jelly Roll. “Back then, we were just fans.”

Riverbeat organizers say they are planning a return to Tom Lee Park in 2025, giving music fans a reason to continue traveling back to one of the world’s great sonic cities.

This article was originally featured on “forbes.com” .

![The countdown is ON, Memphis! We’re officially 30 days out from the @unitememphis 5K + 1-Mile Walk/Run—and this year, we’re stepping into unity on 901 Day 🙌🏽

📍 Monday, September 1 | National Civil Rights Museum

🕘 Start time: 9:01AM

🎶 Food, music & fun to follow

Whether you’re walking or running, this isn’t just a race—it’s a movement. And there’s no better time to join in than now. 👟✨

🎓 COLLEGE STUDENTS: Be one of the first 100 to register using your .edu email with promo code NEXTGENUNITE and your ticket is just $10 (that’s a $32 savings 👀). Limit 2 per person, so tell a friend!

Let’s walk. Let’s run.

Let’s #UniteMemphis 💛

🔗 [link in bio]](https://wearememphis.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/526805187_18335272954206022_6056852028660485499_nfull.webp)