The Tennessee city has one of the richest cultural legacies in the US. But for its new generation of creatives, this can be both a blessing and a curse.

The more you learn about the history of African American music, the more you realise that just about every genre of music, no matter how white it subsequently became (techno, for instance, or heavy metal), can be traced back to Black culture in the United States. As much as any other city, Memphis exemplifies this tradition. From the earliest days of delta blues through to soul music and its thriving contemporary hip-hop scene, it has, for over a century, been an incubator of world-class talent. Alongside this glittering past, its legacy has a darker side: it was a historic centre for the slave trade, and later the site of the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. History, both triumphant and tragic, bears down on Memphis. Today, a new generation of creatives is working with that legacy, or subverting it, and making it once again one of the most exciting cities in the US.

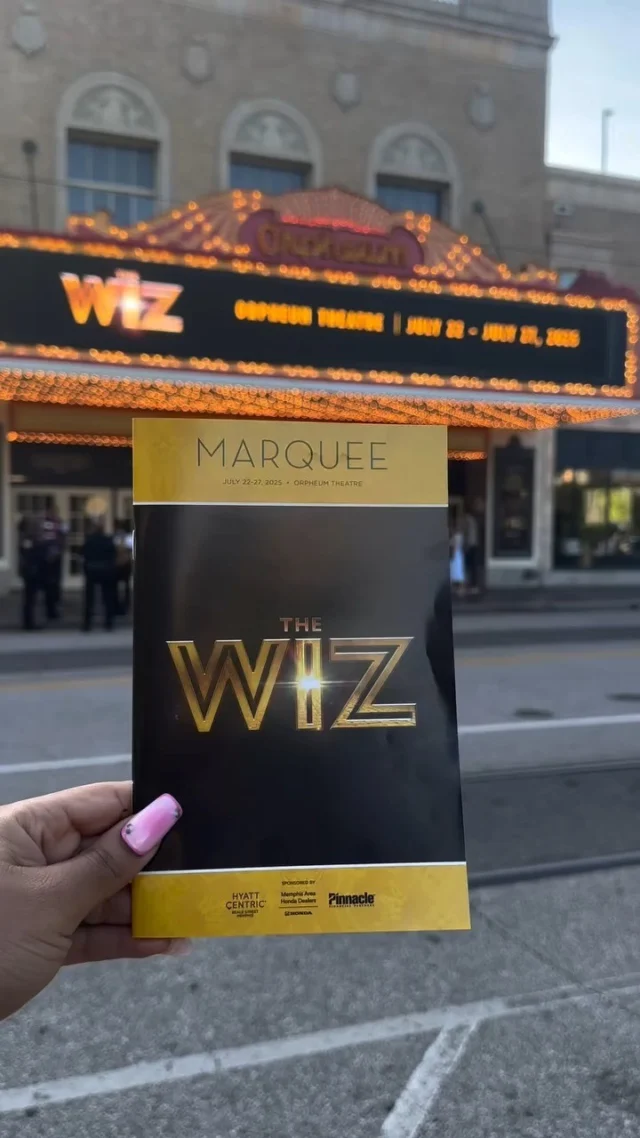

When it comes to musical heritage, Memphis lays a claim to being of the world’s most significant cities. To start with the obvious, there’s Elvis: Graceland, his mansion on the edge of the city, is the second-most visited home in the US after the White House. Thanks in part to the Paul Simon song of the same name, which positions it as a pilgrimage site – somewhere which offers redemption to lost souls – I was expecting to have an epiphany when I was there, some kind of communion with the spirit of Americana. It was probably a self-fulfilling prophecy, but I kind of did. Graceland is extremely kitsch: this was probably the last era when multimillionaires designed their homes based on their most childish whims – monkey statues, clown figurines, stained glass peacocks – instead of hiring an interior designer for something minimalist and tastefully Scandinavian. But the place feels strangely sacred, too: out by the swimming pool, beneath a statue of Jesus with ‘PRESLEY’ written across the bottom, I saw a middle-aged man trying not to cry as he leaned over and tenderly rapped his knuckles against Elvis’s grave.

Elvis might still be Memphis’s most globally famous export, but he himself was drawing on (some might say appropriating) a rich tradition of African American music which had been thriving in the city for decades. Memphis is known for good reason as ‘the home of the blues’, as well as being the site of Stax Records – a label which, along with Motown, gave rise to the explosion of soul music in the 60s and birthed stars like Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes and Albert King. While the label declined in the 1970s, today you can visit the Stax Museum of Modern Soul, which traces the roots of the genre from the African American spirituals which emerged during the slavery era (as you walk in you’re greeted by an enormous reconstruction of a 19th-century church) through to the heyday of the 60s, when the glamorous high point of soul came alongside the struggle for civil rights: you can see guitars, costumes, and Isaac Haye’s gold-plated Cadillac rotating on a spinning plate.

While you won’t find any museums dedicated to it, Memphis is also an important centre of hip-hop. Three 6 Mafia, to offer one local example, are often cited as one of the most influential groups within the last 20 years. “I think one of the things that people forget is that the sound that dominates hip hop today is a sound that originated in Memphis,” Rachel Knox, Senior Program Officer at the Hyde Foundation, a non-profit which supports cultural innovation in the city, tells Dazed. “I think it’s a bit frustrating for Memphians that Atlanta has claimed a lot of that sound, because it originated in Memphis.”

The city’s tourism industry relies heavily on its music heritage: on Beale Street – once considered the Harlem of the South – you’ll find scores of bars playing live blues music amid a sea of elaborate neon-lit signs. Quite a few people I spoke to dismissed the area as a trap for white tourists, which seemed about right. It felt like a theme park version of itself, rather than a place where exciting things are still happening. While Memphians are proud of their music history, some feel it threatens to overshadow what’s happening now; that the city is more concerned with selling alcohol, hotel rooms and Elvis merch to tourists than supporting the next generation of artists. According to James Dukes, a music producer who founded record label and creative agency UNAPOLOGETIC. the powers-that-be are reluctant to accept the role that hip-hop now plays in Memphis’s cultural scene.

“Black musicians and creatives are the driving force of everything cool that comes out of this place,” he says. “What tends to work against us is the fact that there’s a church on every block creating new musicians at any given moment, and therefore, to the people who would use us as batteries, we seem easily replaceable.” When Memphis’s music history is only utilised to promote tourism, it risks becoming less of an asset and more of an albatross for the city’s Black creative scene today. “Do I think there’s a tension between the heritage industry and the music scene now? Yes, it’s a dumpster fire of tension,” Dukes says. In terms of demographic, Memphis is a majority-black city, but as Dukes sees it, whether the people in power are willing to accept that fact remains in doubt.

![The countdown is ON, Memphis! We’re officially 30 days out from the @unitememphis 5K + 1-Mile Walk/Run—and this year, we’re stepping into unity on 901 Day 🙌🏽

📍 Monday, September 1 | National Civil Rights Museum

🕘 Start time: 9:01AM

🎶 Food, music & fun to follow

Whether you’re walking or running, this isn’t just a race—it’s a movement. And there’s no better time to join in than now. 👟✨

🎓 COLLEGE STUDENTS: Be one of the first 100 to register using your .edu email with promo code NEXTGENUNITE and your ticket is just $10 (that’s a $32 savings 👀). Limit 2 per person, so tell a friend!

Let’s walk. Let’s run.

Let’s #UniteMemphis 💛

🔗 [link in bio]](https://wearememphis.com/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/526805187_18335272954206022_6056852028660485499_nfull.webp)